Two years ago, frustrated by the desultory and scattershot progress in making New York’s streets safer and more pleasant, Curbed asked a team of volunteer architects and consultants led by WXY to imagine a thoroughly reengineered Third Avenue as a model for the rest of the city. The stretch they came up with seemed like a fantasy then and doesn’t exist now, but a different section of the avenue is getting a makeover, and many of the elements we featured are appearing elsewhere, adding up to creeping yet visible change. It can’t come soon enough: Drivers still slam into pedestrians, bikes, and cars with appalling regularity and horrific consequences. Last year, car crashes killed 267 people, including 132 people who were just walking along. And that doesn’t count the maimings, brain damage, and trauma among those who survived. This year is shaping up to be marginally less lethal.

So a slow-moving wave of streetscape improvements is cause for both celebration and impatience. Bit by bit, the Department of Transportation is updating them, using an ever-more-precise tool kit. The pandemic’s Open Streets program, patched together at first with movable fences and lemonade stands, has borne a new set of permanent transformations, fitted out with measures to tame cars, attract (and slow down) bikers, relax pedestrians, and elide the difference between sidewalk and street. Admittedly, the latest retoolings leave New York stuck in the bush league compared to European pioneers like Utrecht or Paris, but they also put it far ahead of other major American cities. The coming of congestion pricing ratchets up the urgency of that transformation.

It shouldn’t be so hard for a world-class city to get streets that work and that people like. Covering the distance from good idea to a few finished blocks can take years of advocacy, design, tweaking, hearings, compromise, rejection, and stalling. Mayor Adams recently put the brakes on the Underhill Avenue redesign, one block short of its completion, ostensibly to gather more “community feedback” but mostly to placate die-hard opponents. It doesn’t help that the most dangerous areas are those where local residents depend on their cars and don’t want the city messing with roadways. “These changes are needed most where there’s the least local advocacy and the most pushback,” says the planner and urbanist Mike Lydon. “And it requires a lot of advocacy, not just to get things started but to get them finished.”

Below, you’ll see the real-city improvements that have taken place in the past two years paired (in most cases) with details from our November 2021 story.

From Open Street to Shared Street

For nearly a mile, from the Williamsburg Bridge to McCarren Park, Berry Street has become the model of the new North Brooklyn shared street. From 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. every day, pedestrians own it and drivers come as guests, put-putting through at a top speed of 5 mph. That peaceable coexistence is baked into the design with newly painted lanes, tan epoxy-and-gravel curb extensions to shape narrower crosswalks and wider turns, and a menu of other improvements. More, please.

Pedestrian Plazas & Avenues for People

The streets revolution began in 2007 when city workers showed up at night with paint, metal tables, and blocks of granite to turn traffic snarls into seating. Massive planters send the same message: Pedestrians welcome; drivers, scram. These days, plazas are an integral part of street redesign; the new one at the corner of Atlantic Avenue and Underhill Avenue is the gateway to the new (nearly completed) bike boulevard.

Similarly, a whole generation of New Yorkers barely remembers what Times Square was like before the Bloomberg administration first filled sections of Broadway with deck chairs and café tables in 2007. Now the city hopes to extend the pedestrian-first aesthetic southward, connecting the Flatiron District to Union Square through a series of complicated block-by-block designs that weave together two-way bike flow, local vehicle traffic, and two-legged multitudes. More tantalizing still, a year after closing a portion of Fifth Avenue in midtown to cars on three Sundays in December, the city is expanding the holiday pedestrian zone (from 48th Street to Central Park), suggesting it may follow up on the idea of making that move permanent.

Two-Way and Extra-Wide Bike Lanes

It’s a well-known phenomenon of highway design that if you add more lanes to ease congestion, traffic flows freely for a little while, until it intensifies back to a standstill. The same principle seems to apply to bike lanes too: The more there are, the more cyclists they attract and the wider they need to be to accommodate all the new bikers — as well as travelers on hoverboards, skateboards, e-bikes, scooters, and mopeds. There are worse problems for a city to have than crowded bike lanes, though, and now segments of Tenth Avenue sport those double-wide lanes, making it possible for cyclists to pass or ride side by side.

A 26-block stretch of 34th Avenue in Queens that started out as an Open Street during the pandemic has evolved into Paseo Park, which one advocacy group calls “New York’s most exciting public space.” The new design turns the avenue into a cycling boulevard running in both directions. Using cheap, largely maintenance-free materials like concrete planters and granite blocks, DOT has widened the existing median and reconfigured intersections, strongly urging (if not quite forcing) bikers to keep the pace leisurely. Cars, on the other hand, get turned away since the two-way flow is interrupted by one-way stretches, causing drivers to detour to adjacent streets. Even after its completion, the project is still generating intense feelings with opponents (but not the FDNY) complaining that the measures prevent fire trucks’ wide turns and endanger more lives than they save.

Traffic Calming: Chicanes and Hugs

Persuading drivers not to speed demands more than just a sign and a camera. Much more effective are built-in measures that signal and actively require drivers to take it easy, like the ones built into the latest iteration of Willoughby Avenue in Brooklyn. Chicanes, where the sidewalk bulges out on one side, then the other, force drivers into a slow slalom. At mid-block hugs, sidewalks widen to create nine-foot-wide bottlenecks, just narrow enough to slow a Suburban to a cautious crawl.

Raised Crosswalks

Now that nearly everyone drives high cars with big blind spots and plenty of lethal mass, crossing the street in front of them has become an extreme sport. For that reason, raised crosswalks have started to pop up around the city, especially at known trouble spots like Hylan Boulevard and Buffalo Street in Staten Island or Bronx Boulevard and Nereid Avenue in the Bronx. Elevating pedestrians, even if only by a few inches, provides better visibility, and the subtle speed-bump lift subliminally alerts drivers to the presence of unprotected bodies. The combination may increase the chances that SUV drivers will see pedestrians as human beings rather than moving obstacles. One beautiful side benefit is that, after a snowstorm, the slush slides away from a raised crosswalk, mitigating the need to vault mounds and lakes.

Bike Ramps

Crossing the city’s waterways by bike remains dicey and often unpleasant because the lanes are narrow, speeds are high, and the approaches are often confusing. But the Port Authority recently completed a pair of new elevated ramps at both ends of the George Washington Bridge that is practically Danish in its ambition to provide bikers with serious infrastructure (and fine views).

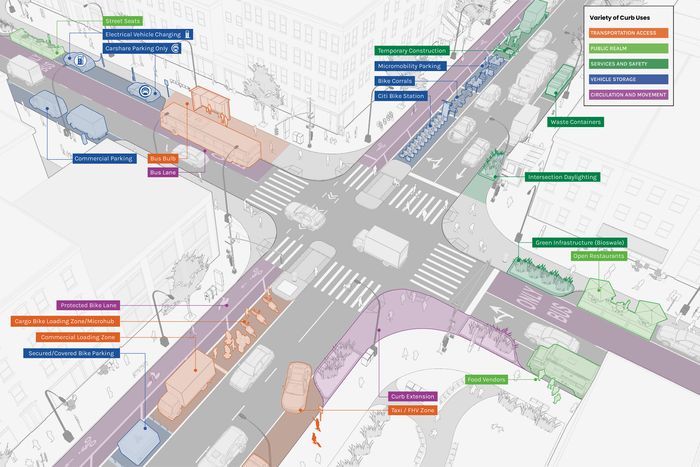

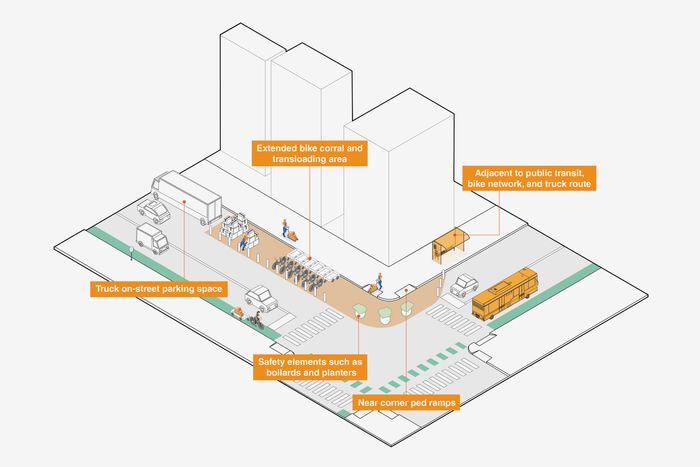

Curbside Management

The border zone between moving traffic and the sidewalk has turned into contested territory. Delivery vans, garbage trucks, parked cars, restaurant sheds, trash containers, cycle lanes, bus stops, Citi Bike stations, taxis, and ambulettes all have a claim to that strip of asphalt. Now DOT hopes to bring some order to the curb via regulation. A new pilot program along Columbus Avenue will weigh whether to install cameras, sensors, and smart meters to keep track of who gets to use the curbside real estate when — and charge accordingly.

The War on Rats

It’s one of the sights that astonish tourists who are under the impression that they’re visiting a world-class city: walls of garbage bags piled on a base of sidewalk slime, entertaining a crowd of feasting rats. After decades of shoulder-shrugging, the city is finally waking up to its streetscape shame and discovering more effective ways of dealing with the 44 million pounds of garbage we all produce every day. “We’ve been playing a massive game of catch-up, and we’re now making real progress,” says Sanitation commissioner Jessica Tisch. “It will change the look and feel of our streets.” To reach that less stinky future, the Sanitation Department is waging the war on rats on two separate fronts: containers and composting.

Restaurants, bodegas, and chain stores are already required to use two-wheeled bins. By next March, all businesses — which generate about half of the city’s daily refuse — will have to do the same. Residents of houses, brownstones, and small buildings (up to nine apartments) will follow next. Violations will trigger a summons. Tisch hopes that by this time next year, 70 percent of the fetid mass will spend the hours between kitchen and garbage truck safely stashed in rigid, lidded bins. In most parts of the city, the sierras of Hefty will be replaced by toy-soldier lines of plastic cans. Sanitation workers will no longer need to heave each dripping sack into the maw of a truck since the bins can be lifted and tipped automatically.

There’s a catch. The new rules won’t apply to large buildings, which churn out the most powerful torrents of trash. High-rises would need armies of those household-size two-wheeled bins and nonexistent alleys or sheds to store them. For now, the Sanitation Department is trying out larger wheeled containers that are left on the street in a pilot program in Hamilton Heights. One problem, though, is that the current fleet of trucks can’t maneuver those bigger boxes, so New York is finally developing the sort of side-loaders that other cities have enjoyed for years.

Universal composting is another powerful tool in cleaning up the streets (and the atmosphere), but that goal has proved elusive. The city has stumbled through more than a decade of tentative, temporary, and voluntary composting programs, which also turned out to be unsustainably expensive. One hurdle is to persuade a city full of ornery individualists to pitch in. “Previous programs were targeted at the truest of the true believers, and there aren’t enough of them,” Tisch says. The key, she says, is to forget about all talk of environmental virtue and focus on a more everyday annoyance: “Now we’re speaking to New Yorkers in their terms. Instead of telling them about methane, we’re talking about rats.” And yet just as it seemed that New York was ready to elevate that ripe form of organic recycling from a hobbyhorse of the few to a civic duty for all, the mayor’s budget cuts forced another postponement. For now, composting is mandatory only throughout Brooklyn and Queens — though until the department can start issuing tickets in 2025, the only enforcement tools it has are pleading and shame.

Bus Islands

For years, East Gun Hill Road in the Bronx has been a notoriously slow slog for buses and a danger zone for pedestrians — it clocked 64 serious injuries and two deaths over four years. An extensive redesign threads new bus lanes through the congested road and includes two full-block boarding islands where passengers can safely wait without having to dodge illegally stopped cars or passing bikes.

Sleeker Streeteries

Curbed’s perfect-street project incorporated a preapproved, kit-built shelter designed by the architecture firm Brandt : Haferd that could be quickly deployed and used for outdoor dining, Greenmarkets, and other uses. That’s not quite what we got, but the new rules for streeteries do bring order, plus sanitary and accessibility upgrades, to the hodgepodge of splintery and rotting sheds. No more jerry-built particleboard rooms with windows or plastic sheeting — just lightweight supports and flexible canopies.